- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in Asia

- in Asia

- in Asia

- within Compliance and Employment and HR topic(s)

The Delhi High Court in a recent decision pronounced on 27 May 2025, upheld the refusal of Indian Patent Application No. 3630/DELNP/2011 filed by Zeria Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. ('Appellant'). The case is one of the few cases thus far, concerning patentability of pharmaceutical intermediates.

Background

Zeria Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., a Japanese company, filed a divisional patent application titled 'A COMPOUND REPRESENTED BY FORMULA (5a)' on May 13, 2011. The application claimed a novel intermediate compound, specifically A 2-[(2-hydroxy-4,5-dimethoxybenzoyl)amino]-1,3-thiazole-4-carboxylic acid methyl ester, which the company asserted was crucial for synthesizing an active pharmaceutical ingredient.

The Indian Patent Office ('Controller') refused the application, citing two grounds, namely, lack of inventive step under Section 2(1)(ja) of the Patents Act, 1970 ('Act'), referencing prior art documents EP 0994108 A1 ('D1') and US 5981557 A ('D2'), and determining that the claimed compound was merely a derivative of a known substance without evidence of enhanced therapeutic efficacy, thereby attracting the exclusion under Section 3(d) of the Act.

The Appeal

The Appellant challenged the refusal and argued that the claimed compound was novel and not obvious to a person skilled in the art, emphasizing that the substitution of a methoxycarbonyl group for an ethoxycarbonyl group represented a significant structural and functional advancement over the prior art documents. The Appellant contended that the Controller had not provided cogent reasoning or specific motivation as to why a skilled person would arrive at the claimed invention based on the cited prior art documents, relying on oft cited precedents such as F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. v. Cipla Ltd. [2015 SCC OnLine Del 13619] and Agriboard International LLC v. Deputy Controller of Patents and Designs [2022 SCC Online Del 940] to support the need for a detailed obviousness analysis.

The Appellant further asserted that Section 3(d) should not apply to intermediate compounds, arguing that the legislative intent of this provision was to prevent evergreening of known drugs, not to restrict patent protection for novel intermediates essential for drug synthesis. The Appellant maintained that intermediates, by their nature, are not directly administered as therapeutics and thus should not be required to demonstrate enhanced therapeutic efficacy; instead, their utility in improving the manufacturing process or enabling the synthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients should suffice for patentability. The Appellant also argued that the prior art document 'teaches away' from the claimed invention, meaning that a skilled person would not have been motivated to make the specific modifications claimed, and therefore, the invention was not obvious.

Arguments submitted on behalf of the Controller, Patent Office

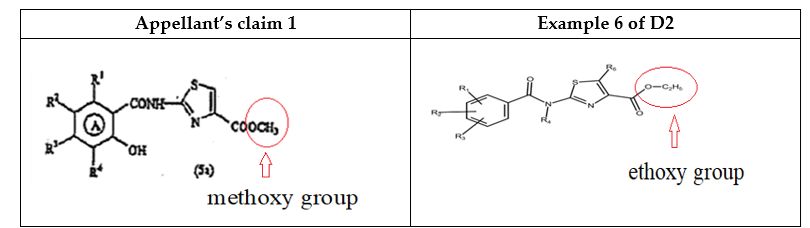

The Controller emphasized that the claimed intermediate compound was only a minor structural modification of known compounds, specifically differing by the substitution of a methoxy group for an ethoxy group, which would be considered an obvious and routine change by a person skilled in the art.

On the issue of Section 3(d), the Controller contended that the application failed to provide data showing that the intermediate compound resulted in a final pharmaceutical product with enhanced efficacy compared to existing compounds. The Controller maintained that, 'claimed compound is a mere discovery of new form in respect of the prior art document D2 and since the claimed compound has no enhanced efficacy in terms of its effect on the process wherein it is used as an intermediate, the claimed compound of the subject application is merely a derivative of the known compound disclosed therein'.

The Controller also argued that the evidence and affidavits submitted by Appellant in support of inventive step and efficacy were insufficient to overcome the statutory requirements, as the experimental data did not demonstrate a significant therapeutic benefit in the final drug product. Thus, the Controller's position was that the claimed compound failed both the inventive step and efficacy criteria, justifying the refusal under Sections 2(1)(ja) and 3(d) of the Act.

The Court's analysis

Turning to the grounds of refusal, the Court assessed the inventive step requirement under Section 2(1)(ja) of Act. The Court reiterated the well-established principle that a mere structural modification—such as the substitution of a methoxy group for an ethoxy group—is generally regarded as obvious if such modifications are routine for a person skilled in the art, particularly when the prior art already discloses closely related compounds. Relying upon the decision in Agriboard International LLC v. Deputy Controller of Patents and Designs, the Court emphasized that the Controller is required to evaluate three key elements: 'the invention disclosed in the prior art,' 'the invention disclosed in the subject application,' and 'the manner in which the claimed invention would be obvious to a person skilled in the art.' The Court found that the Controller had duly considered both the subject matter of the prior art and the claimed invention, specifically identifying D2 (Example 6) as the closest prior art. Accordingly, the Court concluded that the objection raised under 'inventive step' was adequately justified and supported by a reasoned analysis.

On the application of Section 3(d), the Court reaffirmed the legislative intent to prevent evergreening by patenting trivial derivatives of known substances. The Court held that even for intermediate compounds, the applicant must demonstrate that the claimed invention leads to a pharmaceutical product with enhanced therapeutic efficacy, not merely improved process yields or synthetic convenience. The Court referenced its own jurisprudence and the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Novartis AG v. Union of India [(2013) 6 SCC 1], which established that efficacy under Section 3(d) must relate to the therapeutic efficacy in the final product, and not merely to intermediate advantages.

The Court also addressed the Appellant's contention that prior art document D1 'teaches away' from the claimed invention, noting that the absence of a direct disclosure of the compound of formula (5a) in D1, or the fact that D1 proposes an alternative reaction, does not inherently establish that the prior art discourages or dissuades a skilled person from arriving at the claimed invention. The Court clarified that the principle of 'teaching away' requires more than the mere presentation of multiple options or the omission of a particular pathway; there must be a clear technical prejudice or an explicit indication in the prior art that would deter a skilled person from pursuing the claimed modification. In the absence of such a technical prejudice or unexpected result, the presence of alternative solutions in the prior art does not render a specific selection inventive. Accordingly, the Court dismissed the appellant's argument on this ground, reaffirming that the existence of multiple approaches in the prior art, without more, is insufficient to establish inventiveness.

Conclusion

The Delhi High Court's decision in Zeria Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. seems to reflect a rigid and arguably somewhat imperfect interpretation of Section 3(d) of the Act, particularly when applied to intermediate compounds. The Supreme Court in Novartis AG v. Union of India (supra) clearly held that 'efficacy means the ability to produce a desired or intended result,' and that in the case of medicines, the test of efficacy must be therapeutic efficacy. Crucially, the Supreme Court emphasized that the test of efficacy depends on the function, utility, or purpose of the product under consideration.

In Zeria's case, the claimed compound is not a therapeutic agent, but an intermediate used in the synthesis of a final drug. Therefore, applying the therapeutic efficacy standard to such a compound is misaligned with the Supreme Court's interpretation. Also, it is important to note that the Controller did not reject the application for lack of therapeutic efficacy per se, but rather held that the compound was a mere derivative of a known substance without enhanced efficacy in terms of its effect on the process. However, this reasoning fails to engage with the actual data submitted by the Appellant, which demonstrated that the compound led to better yield, higher purity, reduced side products, and faster synthesis of the target molecule.

In fact, it is curious that although the Court cites the decision of the Hon'ble Madras High Court in Novozymes v. Assistant Controller of Patents & Designs [(T) CMA (PT) No.33 of 2023 (OA/6/2017/PT/CHN)] but fails to apply the reasoning in the said decision to comparable facts in the instant case. In the said decision, the Madras High Court in the context of 'enhancement of efficacy', whilst relying upon the Supreme Court decision in Novartis AG v. Union of India (supra) held that there is no limitation for the enhancement to be in relation to any specific type of efficacy because the test of efficacy would be different depending on the product's function, purpose or utility. In the facts of that matter, the Court disagreed with the Controller's conclusion that the enhancement of the known efficacy should be limited to enhanced hydrolysis of phytate, resulting in improved breakdown of the indigestible form of phosphorous to a digestible form. The Court instead held that increased thermostability precludes denaturation and enables production, storage and sale in pellet form; it enhances the known efficacy of the enzyme in aiding digestion. Similarly, in the instant case, the insistence by the Controller and the Court that the intermediate's efficacy is also to be assessed on the same touchstone of efficacy as that of a therapeutic drug, appears incorrect.

Moreover, the Controller's analysis appears to conflate the claimed compound with the hydrochloride form of the final product, despite the fact that the subject application relates to the process for preparing the compound of formula (7), and its hydrochloride form. The Court did not clearly address whether the Appellant's affidavit and supporting data were properly considered, nor did it deliberate on whether the claimed compound truly qualifies as a derivative of a known compound under Section 3(d), especially in the absence of a known efficacy baseline for comparison.

On the issue of inventive step, the Court reiterated the need for a technical advance or unexpected result but dismissed Zeria's evidence of process improvements as routine. This overlooks the principle that hindsight bias must be eliminated in assessing obviousness, and that objective data—such as improved yield and purity—should be given due weight. The Court's reliance on structural similarity alone risks reducing inventive step analysis to a formulaic exercise, ignoring the functional and process-related contributions of the claimed invention.

In conclusion the judgment seems to be a misstep since it extends the therapeutic efficacy requirement to intermediates, contrary to the Supreme Court's ruling, and by undervaluing innovations in the area of intermediates for inventive step analysis. This approach could discourage patent filings for valuable intermediates, which play a critical role in pharmaceutical development, and calls for a more nuanced and purpose-driven interpretation of Section 3(d) in future cases.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.