- within Finance and Banking topic(s)

- in India

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit and Law Firm industries

- within Finance and Banking, Media, Telecoms, IT, Entertainment and Corporate/Commercial Law topic(s)

Introduction

The United Arab Emirates has, over recent years, moved decisively from a fragmented, product-by-product approach to a coherent licensing and supervision framework for payment services. For onshore UAE, the principal regulator is the Central Bank of the UAE ("CBUAE"), which sets the entry conditions, prudential safeguards, conduct standards and supervisory expectations applicable to Payment Service Providers ("PSPs") offering retail payment services in the State.

At the centre of this framework sits the CBUAE's Retail Payment Services and Card Schemes Regulation (the "RPSCS Regulation"), issued under Circular No. 15/2021 and in force from 15 July 2021. The RPSCS Regulation establishes a structured regime for (i) licensing of PSPs for specified retail payment services, (ii) ongoing requirements around governance, risk management, technology and outsourcing, (iii) consumer protection standards (including safeguarding of funds in transit and liability/refund mechanics), and (iv) enforcement tools available to the CBUAE.

This article summarises the legal basis, regulatory perimeter, licensed activities, licensing categories/capital, and the core compliance pillars a PSP must design for when entering or operating in the UAE market.

Statutory authority and regulatory mandate

The CBUAE's mandate to license and supervise regulated financial activities (including payment services) is anchored in Federal Decree-Law No. (6) of 2025 Regarding the Central Bank, Regulation of Financial Institutions and Activities, and Insurance Business (the "2025 CBUAE Law"). Among other things, the 2025 CBUAE Law repealed and replaced the prior central bank and financial institutions framework under Federal Decree-Law No. (14) of 2018 (and also consolidated aspects of insurance supervision into the same legislative architecture).

As a practical matter, the CBUAE's statutory powers are operationalised through "Level 2" instruments such as the RPSCS Regulation, which translate the high-level legislative mandate into licensing conditions, prudential safeguards, conduct standards, reporting expectations and sanctions for PSPs.

Free zones (important boundary): Financial services activity conducted wholly within the Dubai International Financial Centre and the Abu Dhabi Global Market is subject to their respective financial regulators; however, offering or promoting retail payment services into/onshore UAE can still trigger CBUAE perimeter analysis depending on the facts, the customer location, and the activity structure.

Primary framework: what the RPSCS Regulation actually regulates?

- Regulated perimeter – nine "Retail Payment

Services"

The RPSCS Regulation regulates nine categories of "Retail Payment Services" listed in Annex I, and (separately) sets rules for Card Schemes. As a baseline, performing these services in the State (and in certain cases, promoting them in the State) is a regulated activity requiring the relevant CBUAE position/permissions. - Critical exclusions

A number of activities are expressly carved out of the RPSCS perimeter. In particular, the Regulation does not apply to: (i) Stored Value Facilities (which are regulated under a separate CBUAE framework), (ii) Commodity or Security Tokens, (iii) Virtual Asset Tokens (as those terms are defined), (iv) "Remittances" (as defined, including the receipt of funds for transfer where neither the payer nor the payee has a payment account in their name), and (v) currency exchange operations where the funds are not held on a payment account. These exclusions are critical for perimeter mapping because a product that "looks like" a payments proposition may fall outside RPSCS and into a different UAE regulatory bucket depending on its actual characteristics and fund flows.

The RPSCS construct is that payment-account issuance is designed to facilitate the execution of payment transactions and the holding of funds "in transit" for settlement, and it is not intended to operate as a stored-value proposition. Accordingly, "wallet-like" products should be analysed carefully: if the commercial reality is that value is stored and maintained (rather than held only for settlement), the Stored Value Facilities framework may be the more relevant perimeter, not payment-account issuance under RPSCS.

Regulated payment services under Annex I (RPSCS Regulations)

Annex I lists the following nine regulated services:

- Issuance and administration of payment accounts – opening and administering payment accounts used for receiving/holding funds in transit, enabling payment transactions, subject to the RPSCS constraints described above.

- Issuance of payment instruments – issuing instruments that enable a user to place payment orders (for example, cards or digital instruments), subject to applicable security and consumer protection requirements.

- Merchant acquiring – contracting with merchants to accept and process payment transactions, including transaction routing/processing and merchant settlement arrangements.

- Payment aggregation – providing aggregation services that facilitate payment acceptance/collection for merchants/beneficiaries via a consolidated interface/arrangement.

- Domestic fund transfer services – domestic transfers within the State, as defined by the Regulation.

- Cross-border fund transfer services – cross-border fund transfers as defined, noting the Regulation's separate exclusion for "Remittance" (which can capture certain classic remittance business models).

- Payment token services – see "Payment tokens" note below; this is an area that has evolved materially through subsequent CBUAE instruments.

- Payment initiation services – initiating a payment order at the request of a payment service user (without necessarily holding the user's account).

- Payment account information services – providing consolidated information on one or more payment accounts (typically via user consent and secure access controls).

Card Schemes: Card schemes are addressed in dedicated provisions of the RPSCS framework, including governance, transparency, reporting and oversight expectations (and are treated as a regulated perimeter distinct from the nine Annex I services).

Licensing structure, categories and the "banks" carve-out

The RPSCS Regulation operates on a licensing-first perimeter: no person may provide, or engage in the promotion within the UAE, of any "Retail Payment Services" listed in Annex I unless licensed by the Central Bank of the UAE or exempt.

The RPSCS Regulation then allocates activities into a four-category licence architecture (Categories I–IV). These categories are not branding labels; they are service-scope gateways that determine (among other things) the applicable capital floor, prudential expectations, and supervisory intensity. A PSP's category is driven by the actual services it intends to provide (and not merely the contractual label applied in customer/merchant documentation).

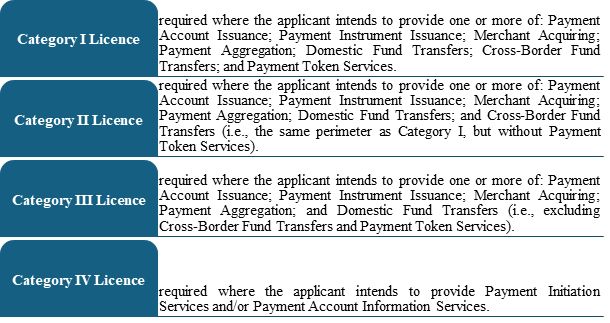

Under Article 3 (Categories of Licence), an applicant must apply for the category corresponding to the services it intends to provide:

Banks carve-out: Banks licensed by the CBUAE are deemed licensed for purposes of providing Retail Payment Services; however, this is not a blanket exclusion from RPSCS operational requirements. The Regulation distinguishes between services a bank may provide without a prior non-objection and services for which the bank must (i) notify the CBUAE and (ii) obtain a CBUAE No-Objection Letter before carrying on the activity. In particular, the bank's ability to undertake certain Annex I services (including merchant acquiring, payment aggregation, payment token services, payment initiation services and payment account information services) is expressly conditioned on notification and receipt of a No-Objection Letter under the RPSCS framework.

As a baseline prohibition, no person may provide, or engage in the promotion in the State of, any Retail Payment Service listed in Annex I unless licensed by the CBUAE or otherwise exempt under the Regulation.

Capital requirements

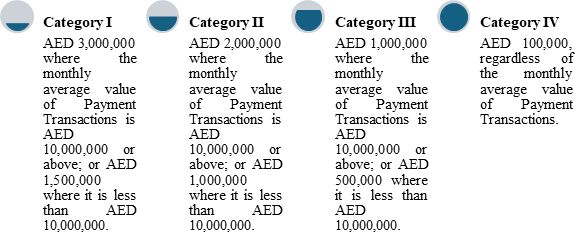

Under the RPSCS Regulation, minimum initial capital is prescribed in Article (6) and is determined by (i) the licence category (Categories I–IV) and (ii) whether the PSP's monthly average value of Payment Transactions is below or at/above AED 10 million. The initial capital floors are:

For the purposes of Article (6), the monthly average value is calculated using the moving average of the preceding three (3) months; where such data does not exist at the time the licence is granted, it is calculated based on the applicant's business plan and financial projections. Applicants must also provide information to the Central Bank on the source(s) of funds constituting the initial capital.

In addition to the entry capital floor, Article (7) requires a PSP to hold and maintain, at all times, aggregate capital funds that do not fall below the initial capital requirements in Article (6), taking into account the relevant licence category. The Central Bank may impose higher aggregate capital funds requirements where it considers this essential in light of the scale and complexity of the PSP's business. Further, where the monthly average value of Payment Transactions (calculated under Article (6)) exceeds AED 10,000,000 for three (3) consecutive months, the PSP must report this to the Central Bank and becomes automatically subject to the higher aggregate capital funds requirements determined by the Central Bank.

Prudential safeguards and consumer protection

The RPSCS consumer-protection framework is more prescriptive than generic references to "ring-fencing". In particular, it draws a clear line between (i) customer funds that are strictly "in transit" for settlement and (ii) funds that remain with a PSP beyond the settlement window triggering specific safeguarding mechanisms and operational restrictions.

A. Customer funds must be "in transit" and safeguarded (24-hour rule)

As a baseline, PSPs must not hold retail payment service user funds except where those funds are "in transit" for the purpose of executing and settling a payment transaction.

If settlement occurs within 24 hours: the PSP must ensure that the relevant funds are not commingled (other than with funds of the relevant retail payment service users) and are insulated against claims of other creditors, including specifically in an insolvency scenario.

If settlement occurs after 24 hours: the PSP must safeguard the funds using one or both of the following mechanisms (meeting the Regulation's conditions):

- Separate escrow account with a bank, with restricted operations such that the funds may only be moved for transfer to the end beneficiary; and/or

- Insurance policy or bank guarantee issued by a regulated insurer or bank, and not within the PSP's group.

Banks acting as PSPs: where a bank provides retail payment services in this context, the RPSCS sets a different safeguarding path—banks are not required to establish an escrow account/insurance/bank guarantee under this specific mechanism, but must instead maintain a separate bank account in the name of the concerned retail payment service users.

B. Liability and refunds for unauthorised transactions

The RPSCS does not set a fixed AED liability cap for unauthorised transactions. Instead, it adopts an allocation-of-liability and mandatory refund framework.

- Baseline position: the PSP is fully liable for any fraudulent or unauthorised payment transaction whether before or after the payer alerts the PSP except where there is evidence that: (i) the payer acted fraudulently; or (ii) the payer acted with gross negligence and failed to take reasonable steps to keep personalised security credentials safe.

- Refund mechanics and timing: where the baseline position applies, the PSP must refund the amount of the unauthorised transaction to the payer and (where applicable) restore the debited payment account to the position it would have been in had the unauthorised transaction not occurred. The refund must be provided as soon as practicable, and no later than the end of the business day following the day the PSP becomes aware of the unauthorised transaction.

- Fraud suspicion exception: the immediate-refund obligation is disapplied where the PSP has reasonable grounds to suspect fraudulent behaviour by the retail payment service user and notifies Central Bank of the UAE of those grounds in writing.

- Payment initiation scenario: where an unauthorised transaction is initiated through a payment initiation service provider, the PSP providing payment account issuance services must still comply with the crediting/refund framework, and the payment initiation service provider may be required to compensate the payment account-issuing PSP for losses/sums paid, on request, where the payment initiation service provider is liable.

- Other errors/complaints: outside the unauthorised-transaction flow, once a PSP concludes an investigation into an error or complaint, it must pay any refund or monetary compensation due within 7 calendar days of that conclusion/instruction; if delayed, the PSP must update the customer on expected crediting time and justification.

C. Transparency of contractual terms

RPSCS hardwires "informed consent" through contractual transparency rules:

- PSPs must provide contractual terms to each new retail payment service user sufficiently in advance of contracting to enable an informed decision, and must provide terms to existing users upon request through accessible channels (including electronic means).

- PSPs must notify users of amendments to terms at least 30 calendar days in advance of the effective date, and users must be able to terminate at no charge if they do not agree with revised terms.

- For "single retail payment service" arrangements, the PSP must provide specified pre-contract information (including, among other items, fees/charges, safeguarding approach, liability allocation, complaint handling, and reporting procedures), with a limited exception where the user requests use of a distance communication method that does not allow pre-contract provision—triggering "immediate" provision after execution.

AML/CFT (risk-based programme aligned to FATF expectations)

RPSCS requires PSPs to comply with applicable UAE AML/CFT obligations and operate a risk-based control environment. This includes identifying, assessing and understanding ML/TF risks, conducting enterprise-level and business relationship–specific risk assessments, and aligning CDD, monitoring and controls to those assessments.

The Regulation also includes explicit "red-line" controls consistent with AML system integrity—e.g., prohibitions around dealing with shell banks/shell financial institutions and restrictions on anonymous/fictitious-name relationships and transactions.

Where relevant (including in relation to tokenised payment services), the RPSCS points PSPs towards alignment with Financial Action Task Force standards/guidance and expects PSPs to incorporate ML/TF trends and typologies into training and risk assessment processes.

Given legislative updates since 2021, PSPs should anchor AML/CFT design and governance to the UAE's current federal AML framework, including Federal Decree-Law No. (10) of 2025 (which repealed and replaced the prior Federal Decree-Law No. (20) of 2018, as amended) and the relevant implementing instruments and supervisory expectations issued by competent authorities.

Technology risk and information security (standards-driven, risk-proportionate controls)

On technology risk, the RPSCS expects PSPs to take into account international best practices and standards, implement controls proportionate to their risk profile, and maintain robust governance around information security, cyber risk, and resilience. In practice, PSPs commonly evidence compliance by aligning their card-data environment and broader ISMS to globally recognised standards (e.g., PCI DSS / ISO 27001) as part of demonstrating outcomes consistent with RPSCS expectations.

Payment tokens

In addition to the RPSCS Regulation, the Central Bank of the UAE has introduced a dedicated regime for "payment tokens" through the Payment Token Services Regulation (issued under Central Bank Circular No. 2/2024). This framework is designed for stablecoin-like payment token activities, and regulates (among other things) payment token issuance, payment token conversion, and payment token custody and transfer as regulated "payment token services", requiring the relevant CBUAE authorisation (licence/registration) before such services (and, importantly, associated promotions) are carried on in-scope.

From a UAE regulatory-mapping perspective, payment tokens are treated primarily as a means-of-payment perimeter: official UAE guidance notes that virtual assets used as means of payment fall within the CBUAE's remit under the RPSCS Regulation, the Stored Value Facilities framework, and (most recently) the Payment Token Services Regulation in cases where fiat value is stored and used for payment purposes; while Securities and Commodities Authority and Virtual Assets Regulatory Authority sit within the wider federal/local virtual asset architecture outside the financial free zones, and the financial free zones (Abu Dhabi Global Market and Dubai International Financial Centre) regulate virtual assets within their respective jurisdictions.

The Payment Token Services Regulation was introduced with transitional arrangements to allow in-scope operators time to regularise their position. In practice, firms should assume a "full compliance" posture unless they can clearly evidence that they fall within any expressly applicable and still-live transition allowance under the relevant CBUAE communications.

PSP licensing lifecycle

A PSP's regulatory "lifecycle" is not limited to obtaining an authorisation. In practice, regulators such as the CBUAE supervise PSPs through a continuous journey from pre-application readiness, through authorisation and go-live controls, into steady-state supervision, and (where necessary) intervention and orderly exit. This lifecycle framing matters because many PSP failures are not "fraud on day one"; they often crystallise later due to liquidity stress, weak safeguarding design, chargeback shocks, processor/bank de-risking, or poor operational resilience. A robust lifecycle approach therefore requires PSPs not only to demonstrate they can operate safely, but also that they can close down safely if needed, without disorderly customer harm.

Typical lifecycle stages (what regulators usually expect):

![]()

- Pre-application readiness: a PSP should be able to evidence governance structure, risk ownership, policy framework, financial model assumptions, and mapped critical vendors/outsourcing chain (including settlement banks, processors, cloud and fraud/AML tooling).

- Application & fit-and-proper assessment: regulators typically scrutinise controllers and senior management capability, compliance resourcing, safeguarding architecture, and whether controls are "operational" (tested) rather than merely drafted on paper.

- Controlled launch / go-live conditions: before scale-up, PSPs are commonly expected to prove core operations work end-to-end settlement and reconciliation integrity, incident handling playbooks, complaints handling, reporting readiness, and the ability to evidence safeguarding in real transaction flows.

- Ongoing supervision: once live, supervision generally shifts to periodic reporting and thematic reviews governance effectiveness, safeguarding performance, AML/CFT alerts and outcomes, customer complaints, operational incidents, audit findings and remediation velocity.

- Intervention triggers: common escalation drivers include safeguarding shortfalls, delayed settlements, repeated operational incidents, high fraud/chargeback rates, capital stress, or control failures in outsourcing chains. Intervention may range from remedial directions and restrictions on activities to heightened monitoring.

- Orderly exit / wind-down: regulators increasingly expect PSPs to maintain credible wind-down capability—documented plan, ring-fenced or otherwise protected customer funds (as applicable), clear customer/merchant communication, timely refunds where due, and controlled termination of vendor dependencies to avoid stranded funds or service disruption.

Conclusion and practical takeaways

The UAE's payments regime is now materially "licensing-first" and outcomes-driven: the CBUAE expects PSPs to enter the market with a clearly defined perimeter, a mapped licence category, and controls that are operationally embedded (not merely documented). For most entrants, the highest regulatory risk is not the absence of a policy—it is a mismatch between (i) how the product actually moves funds and allocates liability and (ii) the licence scope and safeguarding mechanics required under the RPSCS framework.

In practice, three themes determine whether a PSP can scale compliantly under the RPSCS Regulation:

- Correct perimeter mapping: classify the model accurately against Annex I and the stated exclusions (particularly around stored value facilities, currency exchange models, and "remittance" as defined). Misclassification of "wallet-like" propositions as RPSCS payment accounts remains a common and expensive error.

- Capital and safeguarding as product design, not checklists: the Article (6) capital thresholds and the Article (7) aggregate capital funds obligation must be treated as ongoing prudential constraints, while the safeguarding framework especially the "funds in transit" principle and the 24-hour rule must be engineered into settlement flows, treasury operations, and contractual terms.

- Controls that survive outsourcing and scale: as PSPs rely on third-party processors, cloud infrastructure, agents and service providers, the CBUAE's expectation is that accountability remains with the PSP. Governance structures, technology risk and information security controls, and AML/CFT programmes must therefore be designed for auditability, monitoring, incident response, and supervisory access across the full outsourced chain.

Finally, payment tokens should be treated as a regulatory overlay rather than a footnote: where a product involves stablecoin-like payment tokens or related "payment token services," the Payment Token Services Regulation may apply alongside (or instead of) the RPSCS perimeter, and the analysis must be aligned to the UAE's wider split of competencies between onshore regulators and the financial free zones.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.