- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

M&A strategy should be high on the priority list of every leadership team in grocery, even for those companies — in fact, especially for those companies — that aren't currently seeking a transaction. The reason is simple: Deal activity is picking up. You may not be thinking about buying another grocer, but another grocer may be thinking about buying you.

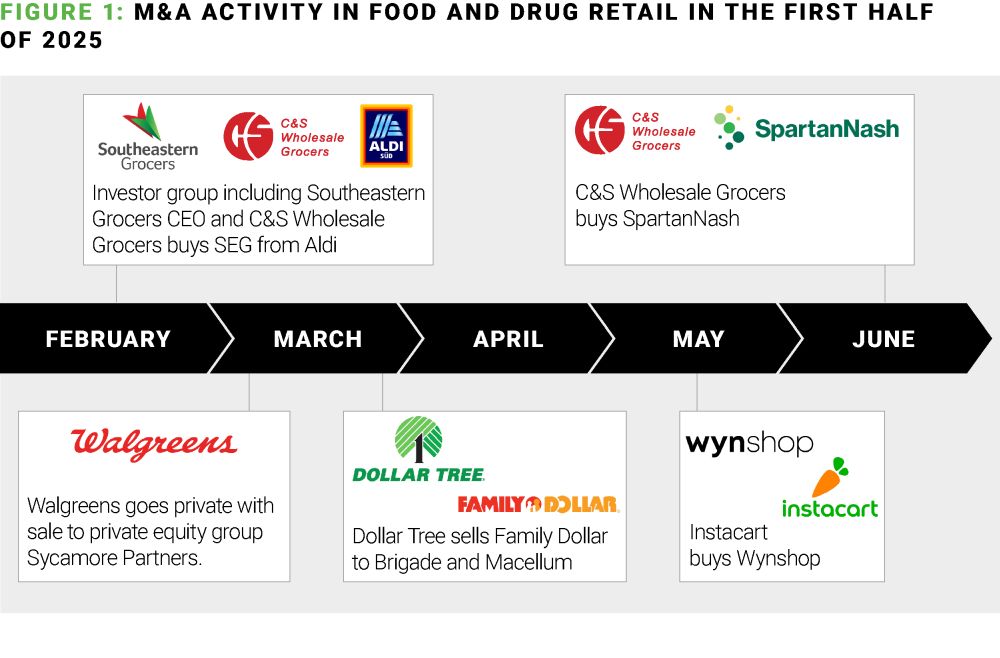

Scale and access to capital always matter, but even more so as tariffs, digital disruption and world events create uncertainty and consumers shift more dollars into discount, mass and club. In the wake of the dissolution of the Kroger-Albertsons merger attempt, we've seen carve-outs, combinations, and take-privates, and we expect more in the near future.

In order to be prepared when opportunities arise, grocers need to assess their businesses, define their strengths, and answer a fundamental question: Are we a buyer or a seller? This is a particularly important exercise because, if a company decides it is a seller, its odds of a positive outcome are much greater if it finds its ideal buyer and makes the case for a deal.

While scale and access to capital are the most commonly cited reasons for grocers to buy or sell, there are plenty of others, and it is often a combination of several that prompts a company to explore its transaction options.

Why grocers sell

To fund major initiatives — When a grocer knows it needs to embark on a capital-intensive, multi-year endeavor to modernize distribution facilities, overhaul IT infrastructure, revitalize a store format, or undertake another massive upgrade, outside funds can be attractive. What compels the grocer in these deals is the opportunity to make efficiency gains that leadership sees as essential to maintaining profitability long-term.

To decrease costs — While there are business model changes that grocers can make to improve price perception and overall value, negotiating on price generally comes down to scale. Grocers that compete heavily with national behemoths like Walmart, Aldi or Dollar General might find greater buying power especially important.

To ensure continuity — A grocer might decide it needs to sell because it doesn't believe its standalone business model is sustainable over the long term but knows that its stores, supply chain and customer base could be leveraged effectively by a stronger company.

For family-owned grocers, any of the above could be a reason to sell, but there are also several motivations unique to this group.

Succession — Whether due to lack of interest or lack of capability, the family doesn't have a viable succession option and wants to close its chapter of leadership.

Liquidity — The family wants some liquidity out of the business. That could mean selling the whole company, or it could mean maintaining a stake while adding a partner.

Vision — The family needs outside perspective to modernize or transform the business, and it is willing to give up some control to lock in that expertise and leadership.

Why grocers buy

To increase returns — A grocer might buy when it recognizes a chance to either lower its costs or make the dollars it's already spending work harder. If a company with a large store support team begins adding smaller chains that don't have that headcount, for example, the company has an opportunity to generate more revenue from its existing cost.

To leverage an operational strength — Some companies have management models that outperform their peers, allowing them to operate profitably where others failed to do so. By implementing an existing superior model, a grocer can quickly upgrade the performance of added stores and drive down costs.

To improve the productivity of an asset — If a company has a distribution center, for example, that has capacity to handle more volume, then adding stores within the right footprint would be another opportunity to reduce fixed costs on a per-store basis. Another example: A grocer may be able to increase sales per square foot by allocating more space either to productive categories it doesn't currently serve or to new product offerings that could come through an acquisition.

To add capability or expertise — Whole Foods Market bought Harry's Farmers Market for its fresh expertise. Walmart bought Jet.com for its online expertise. Amazon bought Whole Foods for its grocery expertise (particularly in fresh). The list could go on. If a grocer identifies a smaller chain with a best-in-class capability that can be adopted and leveraged as a differentiator, an acquisition can be a way to advance a strategically important part of the business.

What good deals have in common

The price is right. — A grocer looking to make an acquisition must have a clear-eyed view of the real value of the other company based on how the grocer intends to leverage it. Organizations often stumble when they do a deal for the sake of doing a deal. When the value equation doesn't make sense, a grocer has to be willing to walk away.

Synergy expectations are based on research, not benchmarks. — Sometimes companies assume there are rules of thumb about what percentage of costs can be cut from every department after a merger, but specifics matter. Doing the complex advance work required to truly understand how the businesses would fit together is essential to make sure the long-term financial rationale for a deal is sound.

The deal isn't expected to fix core business challenges. — A forgettable brand, a lackluster store experience, or a faulty pricing structure won't be automatically remedied by a change in ownership. Every fundamental problem still needs a solution, and awareness of any weaknesses going into a deal is key so expectations and opportunities are clear early on.

The benefits of a proactive approach to M&A

Thinking through M&A strategy forces a company to reckon with reality. Is it a strong enough business to be a buyer? What would make it attractive as a seller? What are the weaknesses that might limit its options? Which companies — perhaps even competitors — have strengths that could be complementary?

In addition to giving the grocer a candid assessment both of its standout capabilities and the areas in which it needs to improve, such an exercise can go a long way toward readiness for the M&A conversations that have become increasingly common this year.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.